Dura

LAUNCH: Saturday 4 October 2025, 7–9pm

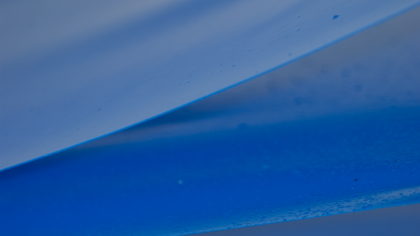

Dura by artist Ciarraí MacCormac contains a new body of work comprising painting, sculpture and works on paper. The polyglot sensibility of paint is what keeps Ciarraí drawn to working with this material. The artist has applied her research into pristine preservations within bodies and operative techniques to give a new lease of life and longevity into her paintings. Within the works there is a layering of liveness and cross sections of surface to create a focus on imagined compartments within the body. The works are constructed from poly materials using primary colours of red, blue and yellow. Their peripheral shapes and use of repetitive accumulation aims to create a sense of dilution throughout the exhibition.

Ciarraí MacCormac, born in Co Antrim N. Ireland. She currently lives in Randalstown and holds a studio at QSS, Belfast. Ciarraí is a Fine Art graduate from Bath School of Art and Design (2014) and she was the inaugural Freelands Studio Fellow for Belfast School of Art (2023–2024). Ciarraí has been the recipient of awards; BEEP Painting Biennial (2024) Shortlisted, AIR Open (2024) Shortlisted, British Contemporary Painting Prize (2024) Long-listed.

I was in a house with many rooms. The sea sweeps through the house.

Sometimes it swept over me, but always I was saved1

– Susanna Clark, Piranesi.

The eardrum is a thin membrane that separates the outer from the inner ear. That structure of the inner ear is called the labyrinth - a complex, maze-like configuration deep inside the ear that houses the organs for hearing and balance. I think about this vibrational skin and micro-architectural network as I lie on my side to use the somewhat medically discouraged Ear Candle: a practice that involves lighting one end of a hollow candle and placing the other end in the ear canal. Proponents claim that the flame creates negative pressure, drawing wax and debris out of the ear canal, which I hope will solve the recent deafness in my left ear. As the gentle heat from the flame transforms me into a recumbent human-body-candle, I think of another candle that I recently lit in a Church, in honour of my Gran, and how perhaps the act of lighting the ear candle feels closer to her in a bodily sense, lying next to her in my thoughts here, in this state of molten waxy inclination and repose.

But since I had no form, I could feel all possible forms in myself… From her present formlessness she would be transformed into one of the infinite possible forms, still remaining herself, however2

– Italo Calvino, Cosmicomics

There is a file on my computer named “Screen Sludge” which consists of a wide collection of stills from films, TV programs, music videos and cartoons – screen grabs of moments where solid body turns liquid. A change of matter, often female, always haptic. I recently learned about a method within Western Animation called a Lustful Melt, a trope involving a character being so enamoured with another, their whole body turns into a puddle of goo, literally turning emotion into matter. Elizabeth Grosz critiques the historical coding of femininity as fluid, excessive, formless, and the lustful melt trope somewhat perpetuates this: women’s bodies as unstable matter, dissolving helplessly under desire. However, for me this intermingling of desire and transformation into one gesture also brings the body’s instability into focus, providing a way to visualise the shifting and sometimes unknown contours of our anatomy. The lustful melt re-plots our outlines, turning the body into a viscose and painterly body-puddle of colours. Puddles are the aftermath of bad weather; shapeshifting; hydrating the soil. Puddles make potholes, puddles have unknown depths; puddles can glitter and shine in their oil slickened elegance. In the cartoon world bodies melt down and can bounce back into form once again, and puddles are portholes to other dimensions.

Indefinite, unspoken peripheral shapes, shifting bodily states and an intrepid exploration of what painting can be defines Ciarraí MacCormac’s new body of work for me, where care and material liveliness tenderly caress and connect. I think about places and spaces I could navigate in full darkness, but that I would struggle to articulate in words. On viewing Ciarraís’ works, my body is placed between them in a way in which leaves me unsure if I need them prosthetically or if they need me structurally. Perhaps it is both.

As the Ear Candle burns, medical forums warn that there is the possibility that stray wax will drip into my ear canal, slowly forming into a solid shape from the hollow internal crevice that I only know by clumsy prodding touch. I envision lying beside Ciarraí’s work titled Sr. The horizontal position allows me to extend my body to its length, and to peer between the stretched blue layers like an accumbent archaeologist, peering up at the glossy underside and catching glimpses of the rougher top side, my breathing in dialogue with the artwork’s horizontality. The top appears to have captured grit, like it has been peeled freshly from its prior surface, stealing some of those traces, and laid to rest here. I rub my thumb and forefinger together, visualising that grit and those folds between the heat of my fingers. This conjures the memory of pulling dried glue from my fingertips when young, examining the tiny synthetic shell of myself just formed, a mould of my fingerprint.

In Exploring Consciousness, Rita Carter says ‘a thing must have a boundary in order for us to name it, categorise it and deal with it… No-thing is, by definition, not a thing at all. But in order to have a concept of it, we have to make it a thing, which means giving it a boundary.’3 Mould making is a form of second skin but is intrinsically tied to multiplication or reproduction. Ciarraí’s skins are never multiplied: they are one off casts from moulds that are more surface than vessel, more painting that sculpture. I think about the exhibition title Dura (the terminology referring to the thinnest membrane around the brain) and all the other unique layers and skins that surround us and make us who we are, even those unseen from the outside. Eva Hesse, Cari Upson, Heidi Bucher, Senga Nengudi, Lynda Benglis are all women who made skins with their artwork, or ‘the skin of the real’4 as Upson referred to her process. But really what links all of these artworks and artists is a deep sense of touch and body and shapeshifting - a radical and soft resistance to rinse and repeat- the making of the work happening in real time with their bodies, to them alone.

With my waxy appendage failing to de-clog, I consult a doctor who uses a digital otoscope to peer onto my ear. My body immediately appearing cavernous on the screen of her monitor, the shapes I have sketched in my mind appear as new terrain to be explored by my eye instead. I expect to see the anatomical equivalent of the London Fatberg, which I saw in the news a few years ago, a liquid turned lumpen accumulation of all the grime we want to pour down our drains, out of sight, steadily growing in the plumbing underground.

In Vivian Sobchack’s notion of “cinesthetic subjectivity,”5 the viewer does not simply watch but feels film with their own body. In this sense, the lustful melt oscillates between humour and violence, eroticism and objectification, producing a cultural allegory in which femininity is coded as unstable matter, simultaneously pleasurable and grotesque. My encounters with Ciarraí and her painting skins have been through screens only: facetime calls, emails of images, google docs of thoughts and drawings and notes. I dearly wish it was otherwise, as I try to summon physicality through image, touch in pixels. The work however maintains an intimacy achieved without proximity and a dedicated belief. I am struck by the similarities of Perspex in the physical work and the screen that I view it through- plastic edges in the artworks that hold the more unstable forms in place like the screen does for Ciarraí’s studio photos. These frames become windows and edges of preservation, that I peer through.

Medieval burial practices (like burial practices in most cultures) manifest a palpable anxiety about the corruption and slime immediately attendant upon death…The holy bodies contained in reliquaries, like bones in the charnel house, were explicitly body – often explicitly body parts – but removed as far as possible from the abhorrent change of corruption. It is worth noting that on the rare occasions when soft tissue was displayed as a relic (for example, the tongue of St. Anthony of Padua), it was claimed to be hard and incorrupt.6

- Caroline Walker Bynum, Christian Materiality

The human body is frequently felt by its absence, instead replaced with objects. Transi tombs are a type of memorial that displays putrefaction as permanence, combining all the movement and process of consumption as a static statue. They suggest there is aliveness of dead matter processed through the things that consume it - such as the bodies of saints who might live on within the worm who eats them. Draped fabric and fragile flesh are ossified in carved stone. Although static in their final display, Ciarrai’s skins are limitless in their defiance of such fossilisation, responsive and adaptive to their environment. I learn that they are bathed, soaked, warmed to become supple and then stand tall on the wall, acts where they are almost ritualistically tended to, to bring them into being. Ciarrai says that handling them when floppy and unsettled is when she feels that they are at their most alive and vulnerable. Interestingly, “flexible” (not “lifelike”) seems to be the most common word associated with incorrupt corpses too.

Our own living bodies, when functioning normally, disappear so to speak, and despite the physicality of what is happening to keep us alive, we are mostly unaware of these processes; our blood pumping, muscles contracting, juices flowing; until something stops working. To dwell within this shifting architecture is to accept its tides, to live with the possibility that its walls will soften, melt, and transform, and that in these moments of transformation other form of ourselves might develop.

The doctor reports that my ears are empty. I am told the cause is perhaps some watery residue deeper in the warren. This unsettles me more than any blockage might have. No lump of wax, no visible obstruction, just a hollow terrain on her screen. I leave wondering if what I sought to extract was never material at all but a shape for absence, a skin for silence, something to press between my fingers and hold up as proof that the body is still there, even when it often slips from view.

---

1 Susanna Clarke, Piranesi (London: Bloomsbury, 2020)

2 Italo Calvino, Cosmicomics, trans. William Weaver (New York: Harcourt, 1968)

3 Rita Carter, Exploring Consciousness, 1st edn (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2002). P.217

4 Kaari Upson, “Emily LaBarge,” Frieze, 25/1 (2025)

5 Vivian Sobchack, Carnal Thoughts: Embodiment and Moving Image Culture (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2004)

6 The Resurrection of the Body in Western Christianity, 200–1336 (New York: Columbia University Press, 1995)